The 93rd Bombardment Group (H)

The Circus Outbound

On

January 28, 1942, less than two months after the United States found

itself plunged into war, the US Army constituted several heavy

bombardment groups to serve as headquarters for the massive force of

Boeing B-17 and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers that were currently

in production to wage war against Germany, Italy and Japan. One of the

new groups would be the 93rd Bombardment Group. A little over a month

later the 93rd activated at Barksdale Field, near Shreveport, Louisiana under the command of 1st

Lt. Robert M. Tate. Later in the month command of the group was assumed

by Lt. Col. Edward J. Timberlake, a West Point graduate and the son of

a career Army officer whose two brothers

were also officers. Timberlake came to the 93rd from the 98th. By October, 1943 all three would be wearing the

stars of brigadier generals and Edward, who went by Ted, would be the

youngest American general since the Civil War. To staff the group's

four squadrons, the 328th, 329th, 330th and 409th Bombardment

Squadrons, a cadre of personnel was transferred in from other groups

and the 93rd began training with the 44th BG, which had equipped with

B-24s the previous year and which had just transferred to Barksdale

from McDill Field, Florida to serve as an operational training unit for

B-24 crews. Training missions were flown out over the Gulf Mexico where

the crews kept a lookout for German U-boats, which were operating in

American waters at the time. By mid-May the group had become

operational and made the first of many moves as it traveled east to Ft.

Meyer, Florida for antisubmarine duty and remained there through July.

During the group's three-month stay in Florida, 93rd crews were given

credit for sinking three U-boats, one of which was claimed by the crew

commanded by Lt. John L. Jerstad, who had been given the nickname

"Jerk."

at Barksdale Field, near Shreveport, Louisiana under the command of 1st

Lt. Robert M. Tate. Later in the month command of the group was assumed

by Lt. Col. Edward J. Timberlake, a West Point graduate and the son of

a career Army officer whose two brothers

were also officers. Timberlake came to the 93rd from the 98th. By October, 1943 all three would be wearing the

stars of brigadier generals and Edward, who went by Ted, would be the

youngest American general since the Civil War. To staff the group's

four squadrons, the 328th, 329th, 330th and 409th Bombardment

Squadrons, a cadre of personnel was transferred in from other groups

and the 93rd began training with the 44th BG, which had equipped with

B-24s the previous year and which had just transferred to Barksdale

from McDill Field, Florida to serve as an operational training unit for

B-24 crews. Training missions were flown out over the Gulf Mexico where

the crews kept a lookout for German U-boats, which were operating in

American waters at the time. By mid-May the group had become

operational and made the first of many moves as it traveled east to Ft.

Meyer, Florida for antisubmarine duty and remained there through July.

During the group's three-month stay in Florida, 93rd crews were given

credit for sinking three U-boats, one of which was claimed by the crew

commanded by Lt. John L. Jerstad, who had been given the nickname

"Jerk."

In May, 1942 the Eighth Air Force transferred from Savannah, Georgia to England to become the headquarters unit for US Army Air Forces units operating in Europe (a small headquarters which became VIII Bomber Command made the move in February.) The 93rd was selected to become the first heavy bomber group equipped with the new B-24 to move to England. The group followed three B-17 groups that moved overseas in July and August. ( It was not the first B-24 group to move to the European Theater. The 98th had moved to Egypt in July where it joined Middle East Air Force and the 1st Provisional Group, a group made up of the B-24s of a special project led by Col. Harry Halverson that had been on the way to China for operations against Japan, and a squadron of B-17s Brereton had brought with him from India.) In preperation for the move, the men of the 93rd moved north from Florida to Grenier Field, New Hampshire where they received a full complement of brand-new B-24Ds, which had been flown there from the factory by ferry pilots. On September 5 the first flight of Liberators departed for England but only got as far as Newfoundland where they were forced to divert due to bad weather. After four days in Newfoundland, 18 Liberators left on a non-stop eight hour flight to Prestwick, Scotland. The flight was the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic by US bombers - the B-17s had to stop off in Iceland due to their much shorter range. One airplane and crew was lost during the crossing, which was made through thunderstorms and icing conditions. For the next month the group was in training at its new base at RAF Alconbury.

On October 8 Col. Timberlake and Major Addison Baker led the group on its first mission, a "milk run" to Lille on the French-Belgian border to attack a steel mill. Although the mission was a "milk run" in comparison to later missions VIII Bomber Command would fly, opposition to and from and over the target was heavy. The group suffered its first combat loss when Captain Alexander Simpson's airplane was shot down. Lt. John Stewart brought his B-24 home with so many holes in it that the crew chief, Master Sgt. Charles Chambers, exploded, "Lieutenant! What the hell have you done to my ship?" Chambers repaired the 200 holes and the crew gave the airplane the name Bomerang because it kept coming back. Part of the crew that was shot down managed to bail out and became prisoners and one, Lt. Arthur Cox, managed to evade and was probably the first Eighth Air Force bomber crewmen to escape to a neutral country, in this case, Spain. Group crews reported from 40-50 German fighter attacks and gunners claimed six shot down, five probables and four damaged. Perhaps surprisingly, the Lille mission was the first Eighth Air Force mission to encounter heavy opposition. All of the previous missions flown by B-17s had truly been "milk runs." John Jerstad cracked everyone up when he commented "that's the worst flak I've ever seen!"

Due to the tremendous losses to U-boats, VIII Bomber Command was directed to mount a series of attacks on submarine pens on the French coast. In November the 93rd flew eight missions, but suffered no losses. That month the 93rd joined by the 44th, which had arrived in England in October and began flying combat in November. In October the 330th BS was detailed to fly antisubmarine missions with RAF Coastal Command. Squadron crews patrolled all the way from Northern Ireland to Algiers on nine-ten hour missions. The B-24s were frequently attacked by Luftwaffe fighters. Maj. Ramsey Pott's crew show down two Junker Ju-88s and claimed another probable over the Bay of Biscay. In one incident Captain Robert "Shine" Shannon, who had flown fighters before he joined the 93rd, took off after a JU-88 he saw in the distance. But although the missions were important in that they caused the German navy headaches, not a single U-boat was ever sighted, much less sunk. On November 13 the group was treated to a visit by His Majesty, King George VI, who was making his first visit to an American installation. He was wearing an RAF marshall's uniform for the occasion. After visiting with the senior group officers in Timberlake's office, the king was taken to the flight line to inspect Teggie Ann, operations officer Maj. Keith Compton's personal airplane, which he had named for his wife, and the group "flagship." Timberlake and Jerstad had flown it on the first mission and it had become the group's lead plane.

Shortly after the group arrived in England Corporal Cal Stewart, who had come over as a radio operator, began publishing a newspaper he named "The Liberator." The former Nebraska newspaperman's talents were quickly realized by Timberlake, who eventually gave him a commission and made him his personal aide. The Liberator was the first military newspaper published in England, and went into print several months before Stars and Stripes and YANK became familiar sights around military posts. Stewart wrote the stories and took the photographs and had the paper printed by a local newspaper after setting the type himself. The paper was not submitted to the censors and the base intelligence officers wouldn't touch it, but they did allow 93rd personnel to send copies back home.

Among

the 93rd personnel was one young airman who stood out. Nebraskan Ben Kuroki

joined the group in April, 1942 while it was still being formed and was

assigned to the 409th as a clerk-typist. He had not experienced

prejudice as he was growing up, but his Japanese ancestry made him a

target after he joined the Army - Ben and his brother had tried to

enlist the day after Pearl Harbor but had to wait for a month until the

Army had decided how to handle Japanese-Americans. A senior 93rd NCO

tried to get rid of him by redlining his name off of the movement order

to Ft. Meyers but he appealed to the squadron adjutant and was

reinstated. He was redlined again on the group overseas order. This

time he appealed to the chaplain. Timberlake himself said that the

young Nisei was going. Ben's clerk duties were in the 409th

orderly room, but he wanted to fly and started spending as much time as

he could out on the flight line, usually hanging out with the armorers.

He was no stranger to firearms; as a boy he had hunted ducks and was a

pretty good shot. The armorers let him work on the guns with them and

he soon was familiar with the Browning .50-calibers. They even let him

test fire the guns. The Air Corps had yet to establish a formal gunnery

training program and pilots picked their gunners from non-flying

enlisted men in the squadron - enlisted crewmembers consisted of the

aerial engineers, who had maintenance training, and radio operator. Ben

finally got his chance to fly when Mississippian Lt. Jake Epting's

tailgunner was medically grounded. Epting picked Ben, and he was placed

on flying status and promoted to sergeant, with an effective date of

December 7, 1942. Ben would go on to complete a 30-mission tour in

B-24s, then went to the Pacific as the only Nisei to fly bombing

missions against Japan in B-29s.

Among

the 93rd personnel was one young airman who stood out. Nebraskan Ben Kuroki

joined the group in April, 1942 while it was still being formed and was

assigned to the 409th as a clerk-typist. He had not experienced

prejudice as he was growing up, but his Japanese ancestry made him a

target after he joined the Army - Ben and his brother had tried to

enlist the day after Pearl Harbor but had to wait for a month until the

Army had decided how to handle Japanese-Americans. A senior 93rd NCO

tried to get rid of him by redlining his name off of the movement order

to Ft. Meyers but he appealed to the squadron adjutant and was

reinstated. He was redlined again on the group overseas order. This

time he appealed to the chaplain. Timberlake himself said that the

young Nisei was going. Ben's clerk duties were in the 409th

orderly room, but he wanted to fly and started spending as much time as

he could out on the flight line, usually hanging out with the armorers.

He was no stranger to firearms; as a boy he had hunted ducks and was a

pretty good shot. The armorers let him work on the guns with them and

he soon was familiar with the Browning .50-calibers. They even let him

test fire the guns. The Air Corps had yet to establish a formal gunnery

training program and pilots picked their gunners from non-flying

enlisted men in the squadron - enlisted crewmembers consisted of the

aerial engineers, who had maintenance training, and radio operator. Ben

finally got his chance to fly when Mississippian Lt. Jake Epting's

tailgunner was medically grounded. Epting picked Ben, and he was placed

on flying status and promoted to sergeant, with an effective date of

December 7, 1942. Ben would go on to complete a 30-mission tour in

B-24s, then went to the Pacific as the only Nisei to fly bombing

missions against Japan in B-29s.

In early December Timberlake was ordered to take his group - less the 329th which had been picked for a special mission - south to North Africa. Timberlake was told that the temporary duty (TDY) would be for ten days; the three squadrons were gone for three months. The crews were told to travel light as they wouldn't be gone long. Ground personnel remained behind in England. One crew from the 330th was lost when their airplane hit a mountain while landing at their temporary base at Tafaroui. Personnel at the base had not been alerted that the B-24s were coming in and no plans had been made to light up the runway. Fortunately, the first flight of Liberators landed just before dark and arranged to have gasoline flares lit alongside the runway. As it turned out, winter rain turned Tafaroui - "where the mud is always gooey" into a sea of mud. Timberlake protested in vain to Twelfh Air Force commander Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle, who had won fame as an air racer before the war then had led a raid on Japan, that the field was impossible but Doolittle insisted that a mission be flown on December 12. When the first airplane to take off, Geronimo, mired up in the mud while taxiing to the runway and broke off the nose gear the planned mission was cancelled. The group flew two missions to Bizerte on December 13 and 14, but Eighth Air Force commander Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, decided that the 93rd could be better utilized with Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton's Ninth Air Force, which included two groups equipped with B-24s operating out of Egypt. The 376th BG included one squadron of B-17s to Spaatz worked out a trade; the Ninth B-17s transferred permanently to Doolittle's Twelfth Air Force and the 93rd was attached to IX Bomber Command. Early on the morning of December 15 the 93rd took off for its new temporary home at Gambut Main, a desolate airfield in the Libyan desert. In his diary Brereton described Gambut as to remote that there was literally nothing there except for one metal building. IX Bomber Command, which was commanded by Ted Timberlake's older brother Patrick, was using it as a staging base for missions further west. They would come in, set up a temporary camp, fly the mission then everything would go back to Egypt. After the 93rd joined IX Bomber Command, the group operations officer, Major Keith Compton, was promoted to lieutenant colonel and transferred to the newly established 376th to take over as group commander. The 376th had been formed overseas from the 1st Provisional Bombardment Group, which Brereton had established to control the HALPRO contingent of B-24s that had been on their way to China and the squadron of B-17s he had brought with him from India in June.

While the rest of the group was in Africa, the 329th was training for a new mission called "Moling." The squadron's airplanes were modified by the installation of newly developed electronic navigation equipment that allowed the crews to operate in inclimate weather. The Moling concept was for the modified bombers to penetrate deep into hostile airspace as intruders. Although the missions weren't expected to cause significant damage, they were planned to disrupt the German air defenses and provoke air raid warnings which would cause factory workers to go to shelters. Up to this point no American bombers had yet penetrated German air space. A 329th crew went out on what would have been the first mission to Germany but after flying across France in clouds, they suddenly broke out into the clear as they neared the frontier. Since they had lost their cloak of clouds, the crew had no choice but to abort the mission. Consequently, a few days later a formation of B-17s had the honor being the first to bomb Germany. The 329th worked with British engineers to refine the navigational equipment, which was designated as H2S and Gee, which the RAF had been using on its pathfinder aircraft. The systems were adopted by the USAAF to equip pathfinder B-24s and, later, B-17s.

The 93rd remained in Libya until late February. During their time in North Africa 93rd crews were credited with sinking seven Axis merchant ships and damaging several others. Their bombs destroyed dozens of German and Italian planes on the ground as well as railroad cars and bridges and supply depots. Missions were flown against German supply depots in western Libya and Tunisia and to European targets in Greece, Sicily and Italy, including Naples. During the group's absence the ground echelon and the 329th had relocated to a new base at Hardwick and was where the group returned. While they were gone YANK newspaper had been established and PIO Cal Stewart invited the press out to Hardwick. Censorship prevented the revelation of unit designations to Stewart invented the sobriquet "Ted's Travelling Circus," using the British spelling with two l's. Group personnel weren't allowed to say where they had been or what they had done, but the 93rd suddenly became notorious, much to the chagrin of the 44th Bombardment Group, which had remained in England, and VIII Bomber Command's B-17 groups. Stewart had been told by an Eighth Air Force publicity officer to "work for the entire Eighth Air Force or else" and The Liberator was renamed "Stars and Stripes" and developed into a large scale overeseas military newspaper enterprise - which is still in existence. One crew, Lt Jake Epting's, which included Ben Kuroki, had crashlanded in Spanish Morroco due to bad weather and the crew was interned in Spain until they were finally released and returned to US control. After he returned to England, Kuroki was interviewed by radio personality Ben Lyon.

During the 93rd's absence, the 329th had often operated on conventional bombing missions in company with the 44th BG, which had become operational in November. The 44th had suffered heavy losses, but most were due to accident rather than enemy action. At the time there were no other B-24 groups in Europe and the new groups that were coming in were equipped with B-17s. The B-24 was a new design that had been developed to replace the older B-17, which had not measured up to the requirements under which it had been originally purchased. The British had refused to accept B-17s under Lend-Lease after an initial test squadron failed miserably, but had opted for the new Liberator instead. Consequently, when war broke out only a handful of B-24s had been assigned to US units as most of the production was going to the RAF and the first new groups equipped with B-17s. By the end of 1943 all new groups were equipping with B-24s but in the spring, that was still in the future.

In May Col. Timberlake left the 93rd and moved up to take command of the 201st Provisional Bomb Wing, which had been created as a command unit for the 44th, 93rd and 389th, which was preparing to move to England from the US. Command of the 93rd went to Lt. Col. Addison Baker, who had been commander of the 328th. May also saw a tragedy when Hot Stuff, the first Eighth Air Force bomber to complete a combat tour, crashed in Iceland. The flight is still shrouded in mystery because Lt. Gen. Frank Andrews, the senior US Army officer in the ETO and an airman, was on board along with several other dignitaries. Gen. Andrews and the other dignatries bumped part of Captain Robert "Shine" Shannon's crew off of the flight, including the copilot. (Another 93rd officer was on board who has not been identified except by name - he may have also been a pilot. Andrews himself was an accomplished pilot and skilled in instrument flight. While commander of the GHQ Air Force, Andrews had pushed for instrument training for all combat pilots.) The airplane crashed in bad weather after making several attempted instrument approaches. No official reason has ever been given for Gen. Andrews trip, but it is believed that he had been called back to Washington for a conference. Andrews was a favorite of US Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall and had been Marshall's first choice to head up the Army Air Corps in 1939, but he had been overridden because of Andrews' outspoken advocacy of the four-engine heavy bomber. Marshall later indicated that he wanted Andrews as the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, but his untimely death led to the appointment of Dwight Eisenhower. Shannon's crew was returning to the States as the first Eighth Air Force crew to complete a combat tour, but it had only been recently that such a tour had even been established. Airmen in Europe were under the understanding that they were there for the duration or they were lost, whichever came first. Army Air Forces chief General Henry H. Arnold visited the 93rd at Hardwick in late April. While addressing the crews, Arnold commented that completion of 25 missions constituted a tour of duty and entitled a man to R&R in the US before reassignment. Several men in the room had already flown more than 25 missions by that time. Shannon's crew was one - they had flown their 31st and final mission on March 31st.

Immediately after the 201st PBW activated the 44th and 93rd were taken off of operations for training. The newly arrived 389th also joined in the training, which was conducted in secret and included hours of low-level practice flying. Rumors spread through the B-17 groups that the B-24s were being removed from combat because they were "no good." It was just that, a rumor. In reality, the B-24s were destined to fly what is now the most famous mission of World War II, a daring low-altitude attack on the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. The operation, which was originally code-named SOAPSUDS, was first discussed at the Casablanca Conference in early 1943. Ninth Air Force commander Gen. Brereton was advised of it, and did not think it was a good idea at the time as the Allies were still heavily engaged in combat operations in Tunisia and were planning to invade Sicily as soon as North Africa was secure. Planning for the mission was underway in Washington under the supervision of Col. Jacob Smart, a project officer assigned to Arnold's staff. In June, after the Allied victory in Tunisia, Brereton was informed that the operation was on, and that his IX Bomber Command would carry it out as the B-17s were inadequate for the task. IX BC would be augmented by the three Eighth Air Force B-24 groups. Brereton recorded in his diary that the Ploesti operation was actually planned to be a campaign consisting of a large-scale attack at low altitude followed by up to eight conventional high altitude missions to complete the destruction of the refinery complex. By July the operation had been given a new name, TIDAL WAVE, and Brereton set up a planning staff which included Timberlake, who had moved to Libya by that time. Brereton had the option of flying the mission at low or high altitude, but decided that a low altitude attack would catch the Germans by surprise. Low altitude attacks by B-24s was not without precedent - crews from the 376th had been making low-altitude attacks in Italy for some time. When Brereton met with the five group commanders and informed them of the plan, he advised them that the low-altitude attack decision was solely his and was not open for discussion.

TIDAL WAVE was not the sole purpose of the TDY of the B-24s from England to Libya. The Allies were planning to invade Sicily on July 9 and the three groups would join with IX BC's two groups on attacks in Italy in preparation for the invasion. On July 19 the five B-24 groups attacked railroad yards in Rome in concert with Doolittle's B-17s and Martin B-26s, which were now part of an Allied Northwest Africa Strategic Air Force under Spaatz' Northwest Africa Air Force. After the Rome mission the five B-24 groups were taken off of operations for TIDAL WAVE, which was scheduled for August 1. The mission almost didn't come off. RAF Air Chief Marshall Arthur Tedder wanted to cancel it when Mussoloni was deposed, but Brereton convinced him that to do so would be a mistake for several reasons. The Axis were getting the bulk of their POL supplies from Ploesti which was reason enough, but Brereton also feared that cancelling the mission would cause a severe morale blow for the crews, who had been training for several weeks.

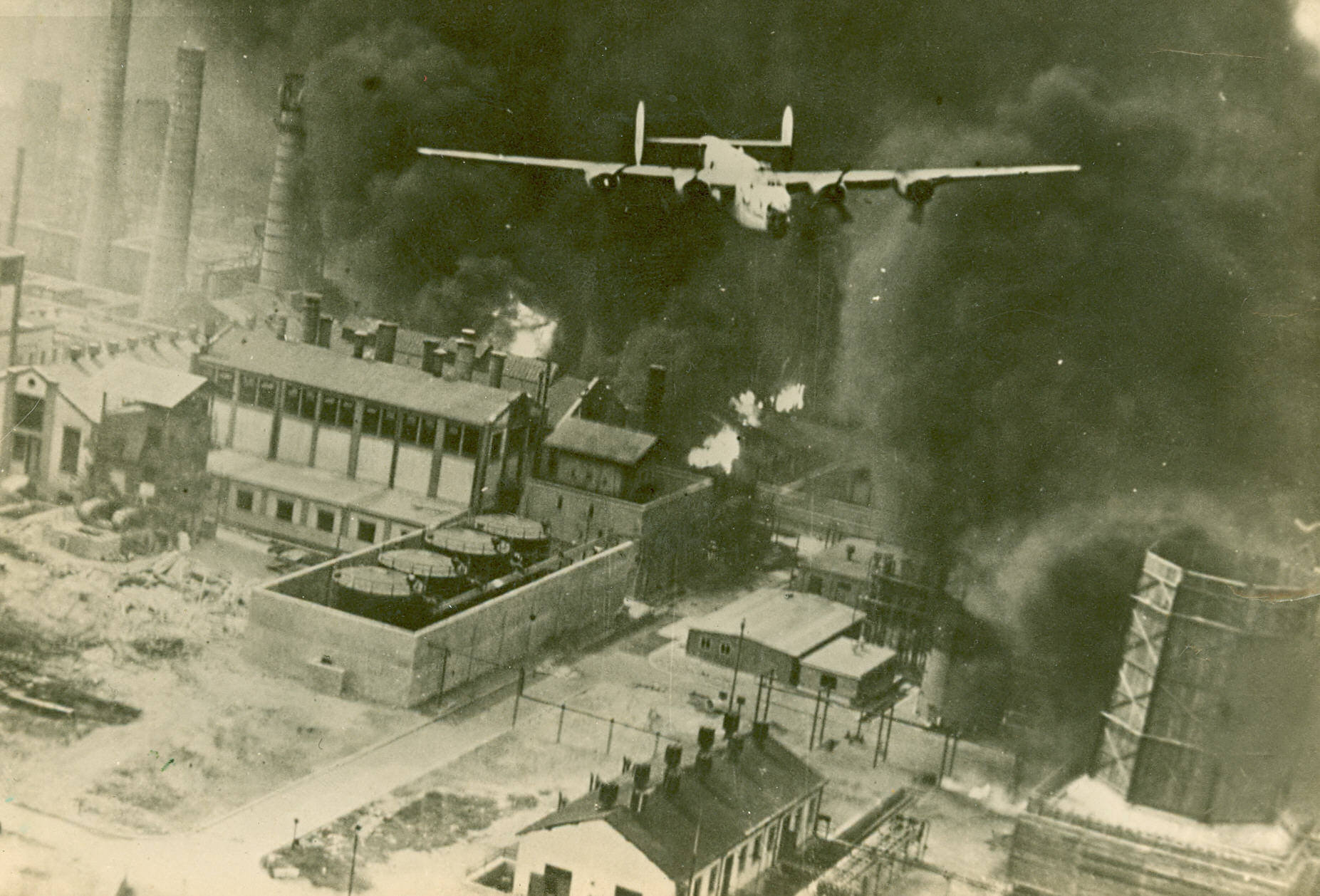

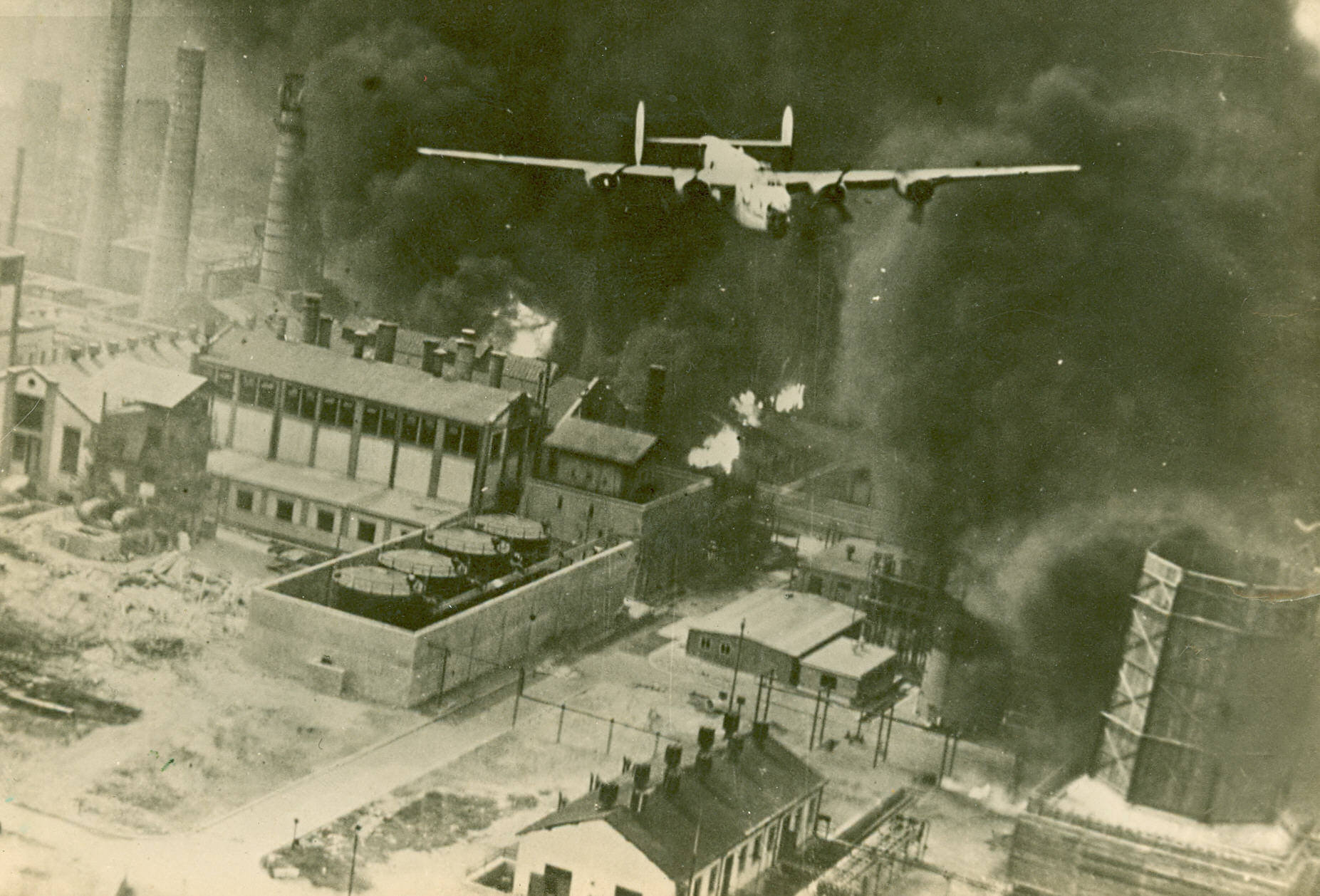

The Ploesti missionis often considered to have been a military disaster, but in truth casualties were no more than those taken by B-17s on high level missions over Germany. The lead group, which was being led by 376th commander Col. K.K. Compton - Compton had stayed in Africa to take command of the newly activated 376th after the 93rd's first African TDY - with IX BC commander Brig. Gen. Uzal Ent on board as an observer, mistook a check point in the summer haze and mistakenly turned about 20 miles too soon and headed toward Bucharest. Lt. Col.

Baker realized the 376th had turned early and after

following the lead group for several miles, decided to break away and

go after the refineries, which he could see in the distance. He was not

in position to hit his assigned target but went after the nearest

complex as a target of opportunity. Baker's

copilot was Maj. John Jerstad, who had moved up with Timberlake to the

201st and had been the principle planning officer for the mission.

Although the mission had been planned in hope of obtaining complete

surprise, the German air defenses had realized that a large mission was

underway and had deducted that the Ploesti oil fields were the likely

targets. Antiaircraft gunners around the complex were on the alert

while German and Romanian fighter pilots were waiting to be scrambled.

Several batteries of automatic antiaircraft (AAA or Triple A) guns had

been installed in

and around the refineries along with a number of large caliber

antaircraft guns, which could be depressed to fire at low-level

aircraft. Barrage balloons loomed over the target. As the Circus

formation approached their improvised target - they

were not in a position to attack the one they had been assigned - heavy

antiaircraft fire came up to greet them. The B-24 gunners - including

Ben Kuroki who was flying in the top turret on Tupelo Lass,

Col.

Baker realized the 376th had turned early and after

following the lead group for several miles, decided to break away and

go after the refineries, which he could see in the distance. He was not

in position to hit his assigned target but went after the nearest

complex as a target of opportunity. Baker's

copilot was Maj. John Jerstad, who had moved up with Timberlake to the

201st and had been the principle planning officer for the mission.

Although the mission had been planned in hope of obtaining complete

surprise, the German air defenses had realized that a large mission was

underway and had deducted that the Ploesti oil fields were the likely

targets. Antiaircraft gunners around the complex were on the alert

while German and Romanian fighter pilots were waiting to be scrambled.

Several batteries of automatic antiaircraft (AAA or Triple A) guns had

been installed in

and around the refineries along with a number of large caliber

antaircraft guns, which could be depressed to fire at low-level

aircraft. Barrage balloons loomed over the target. As the Circus

formation approached their improvised target - they

were not in a position to attack the one they had been assigned - heavy

antiaircraft fire came up to greet them. The B-24 gunners - including

Ben Kuroki who was flying in the top turret on Tupelo Lass,

Epting's new B-24 - engaged the flak towers to suppress the fire. The

converging tracers hit the gasoline and oil storage tanks on the

outskirts of the refinery and set them afire. While still two miles

from a practical bomb release point, Baker's Hell's Wench

was hit several times and set on fire. It was reported later that Baker

had said the night before that even if his airplane was hit, he'd make

every effort to lead the group over the target - he made good on his

word. The pilots jettisoned the bombs to lighten the load so the

stricken Liberator could keep flying and kept going. After passing over

the refinery Baker and Jerstad pulled their airplane into a steep climb

to gain altitude to give the crew a chance to bail out, then the

airplane fell off on a wing and crashed in a field. Other crews could

see flames in the cockpit of the stricken B-24 when it went down. For

their actions, Baker and Jerstad were both awarded the Medal of Honor,

or the Congressional Medal of Honor as it was commonly known at the

time. All told, 53 Liberators failed to return from the mission,

although that number includes eight that made their way to Turkey where

the airplanes were confiscated and the crews returned. The 93rd lost

eleven. Results of the missions were actually much better than is

commonly reported. Initial estimates were that 60% of the refineries'

capacity was destroyed, although this estimate was downgraded to 40%.

One refinery never returned to operation. (Hundreds of thousands of

words have been devoted to the Ploesti mission, with most authors

trying to come up with an "explanation" for the "wrong turn." They

can't see the forest for the trees. The mission was flown, the target

was hit and severely damaged - which is all that can really be expected

from any military operation.)

Epting's new B-24 - engaged the flak towers to suppress the fire. The

converging tracers hit the gasoline and oil storage tanks on the

outskirts of the refinery and set them afire. While still two miles

from a practical bomb release point, Baker's Hell's Wench

was hit several times and set on fire. It was reported later that Baker

had said the night before that even if his airplane was hit, he'd make

every effort to lead the group over the target - he made good on his

word. The pilots jettisoned the bombs to lighten the load so the

stricken Liberator could keep flying and kept going. After passing over

the refinery Baker and Jerstad pulled their airplane into a steep climb

to gain altitude to give the crew a chance to bail out, then the

airplane fell off on a wing and crashed in a field. Other crews could

see flames in the cockpit of the stricken B-24 when it went down. For

their actions, Baker and Jerstad were both awarded the Medal of Honor,

or the Congressional Medal of Honor as it was commonly known at the

time. All told, 53 Liberators failed to return from the mission,

although that number includes eight that made their way to Turkey where

the airplanes were confiscated and the crews returned. The 93rd lost

eleven. Results of the missions were actually much better than is

commonly reported. Initial estimates were that 60% of the refineries'

capacity was destroyed, although this estimate was downgraded to 40%.

One refinery never returned to operation. (Hundreds of thousands of

words have been devoted to the Ploesti mission, with most authors

trying to come up with an "explanation" for the "wrong turn." They

can't see the forest for the trees. The mission was flown, the target

was hit and severely damaged - which is all that can really be expected

from any military operation.)

After the Ploesti mission, the five groups stood down so their airplanes could be repaired. Dozens of new engines were flown in from depots on Air Transport Command C-87 transports - the C-87 was derived from the B-24D. Just because Ploesti had been attacked did not mean that the Eighth AF B-24s were through in the Mediterranean. In fact, the plan had been to mount a campaign against the oil fields but ACM Tedder notified Brereton that the campaign would be delayed and the focus would shift to attacks in Southern Europe. It wasn't until the following April that attacks on Ploesti were resumed by B-17s and B-24s assigned to Fifteenth Air Force, which activated in Italy a few months after the low-level attack. IX BC flew two missions against the aircraft factories at Weiner-Neustad, Austria. Col. Leland Fiegel, who had been with the 93rd in the US, was brought over to take command of the grouip. After an attack on Naples on August 21, the three Eighth Air Force groups were released to return to the UK. Less than a month later Timberlake took his wing back to North Africa, this time to Tunis, for operations against targets in Italy and Austria. The Eighth Air Force B-24s operated out of Tunisia until the end of September then returned to England, this time for good.

For the 93rd, the group was entering what was essentially a brand new war. Nearly all of the group's original combat crews had returned home after completion of their combat tours with only those who had moved to staff positions remaining. The ground crews were not subject to rotation and remained, seeing their airplanes flown by one crew after another as they finished their tour and returned home. A major reorganization took place as the Ninth Air Force moved to England to become a tactical air force to support the upcoming Normandy invasion - Ninth would eventually become the largest US air force in history. It's B-24s transferred initially to Twelfth, then became part of a new Fifteenth Air Force commanded by Jimmy Doolittle. More and more B-24 groups were arriving in England and Second Air Division was established to control them. The 93rd became part of the 20th Combat Bombardment Wing, one of three wings equipped with B-24s. In early 1944 Eighth Air Force headquarters was elevated to become United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, a new organization that would control all strategic air operations in the European Theater. VIII Bomber Command was elevated to air force level and redesignated as a new Eighth Air Force. Both units activated in February, 1944. In the reorganization Eighth Air Force commander Ira Eaker was promoted to lieutenant general and sent to the Mediterranean to replace Tedder, who had been appointed deputy commander under Eisenhower of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Forces in Europe. Jimmy Doolittle was brought to England to take his place. By June 6, 1944 Eighth Air Force B-24 strength had built up to nineteen groups, only four less than the twenty-three groups of B-17s. Army Air Forces intentions were to replace all B-17s with B-24s but for some reason Doolittle opposed the move and wanted to convert Eighth Air Force entirely to B-17s. More replacement B-17s were arriving in England than needed so he took them and began converting the B-24 groups in the 3rd Air Division. His plan to convert all groups was thwarted by a cessation of B-17 production and the impending end of the war, with the corresponding decline in importance of strategic bombardment.

The war effort in Europe in late 1943 was now focusing on making preparations for the upcoming Normandy Invasion. In his New Years message to Eighth Air Force, Arnold had stated that the mission was to "destroy the German air force in the air, on the ground and in the factories." Throughout 1943 bomber missions into Germany had been flown without escort, and mounting casualties led to a suspension of deep penetration missions until escort fighters became available that could make their way all the way to the targets. Such aircraft were under development as external fuel tanks were developed for the Republic P-47s that were serving as the primary escorts. Long-range Lockheed P-38s, all of which had been diverted to Africa, became available for escort duty from England. R&D expert Brig. Gen. Ben Kelsey had spearheaded the development of a new version of the North American P-51 Mustang that also had the range to go all the way to Berlin and other targets deep in Germany. However, it is a myth that bomber losses began declining with the advent of the escort fighter, particularly the P-51. In fact, losses began increasing. By April 1944, losses exceeded 400 airplanes. The B-24 had also undergone development. In an effort to ward off the head-on attacks favored by German, Italian and Japanese fighters, a new nose turret installation had been developed to replace the glass nose on the D-models. The new turrets produced additional drag and reduced the B-24s airspeed by about 20 MPH, but the Liberators were still a good 20 MPH faster than the B-17G, and could carry a much larger payload over greater distances.

In preparation for the invasion, Spaatz' USSTAF planned a massive campaign of attacks on the German aircraft industsry by Eighth and Fifteenth Air Force B-17s and B-24s, a campaign that came to be known as "Big Week." New bomber tactics involved the use of pathfinder B-24s as lead airplanes in bomber formations. The pathfinder airplanes, which in the 93rd were assigned to the 329th, were equipped with radio navigational equipment and radar and radar operators and radar bombardiers were included in their crews. Although Eighth Air Force senior officers still talked about "precision" bombing, it had actually adopted the British model of using pathfinders to find the target. The difference was that daylight missions depended on lead crews who would determine the release point, with the rest of the bombers in the formation dropping when they did. British missions were flown exclusively at night and the pathfinder crews lit up the target with incindaries and flares. Incindiary bombs were also included in B-17 and B-24 bomb loads.

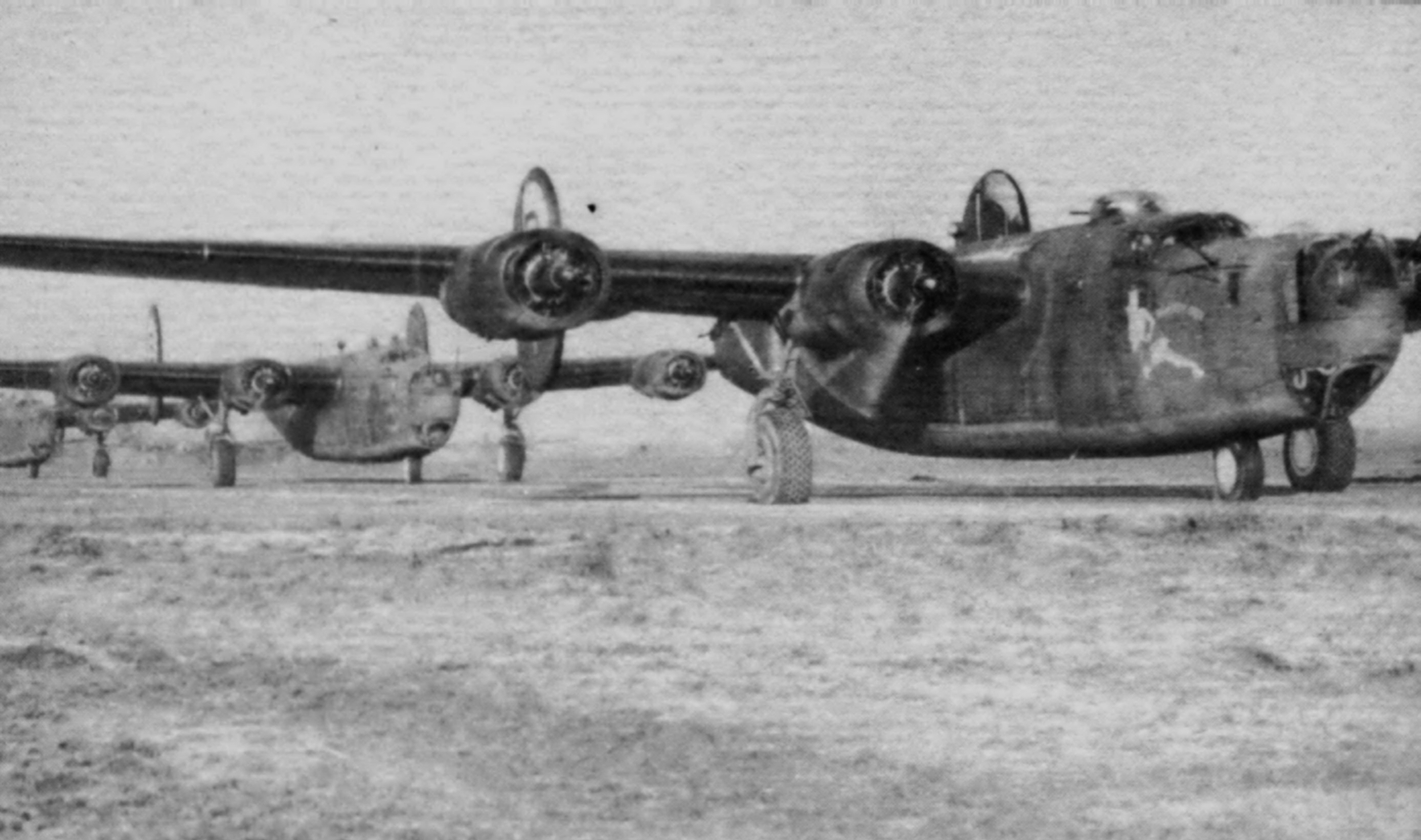

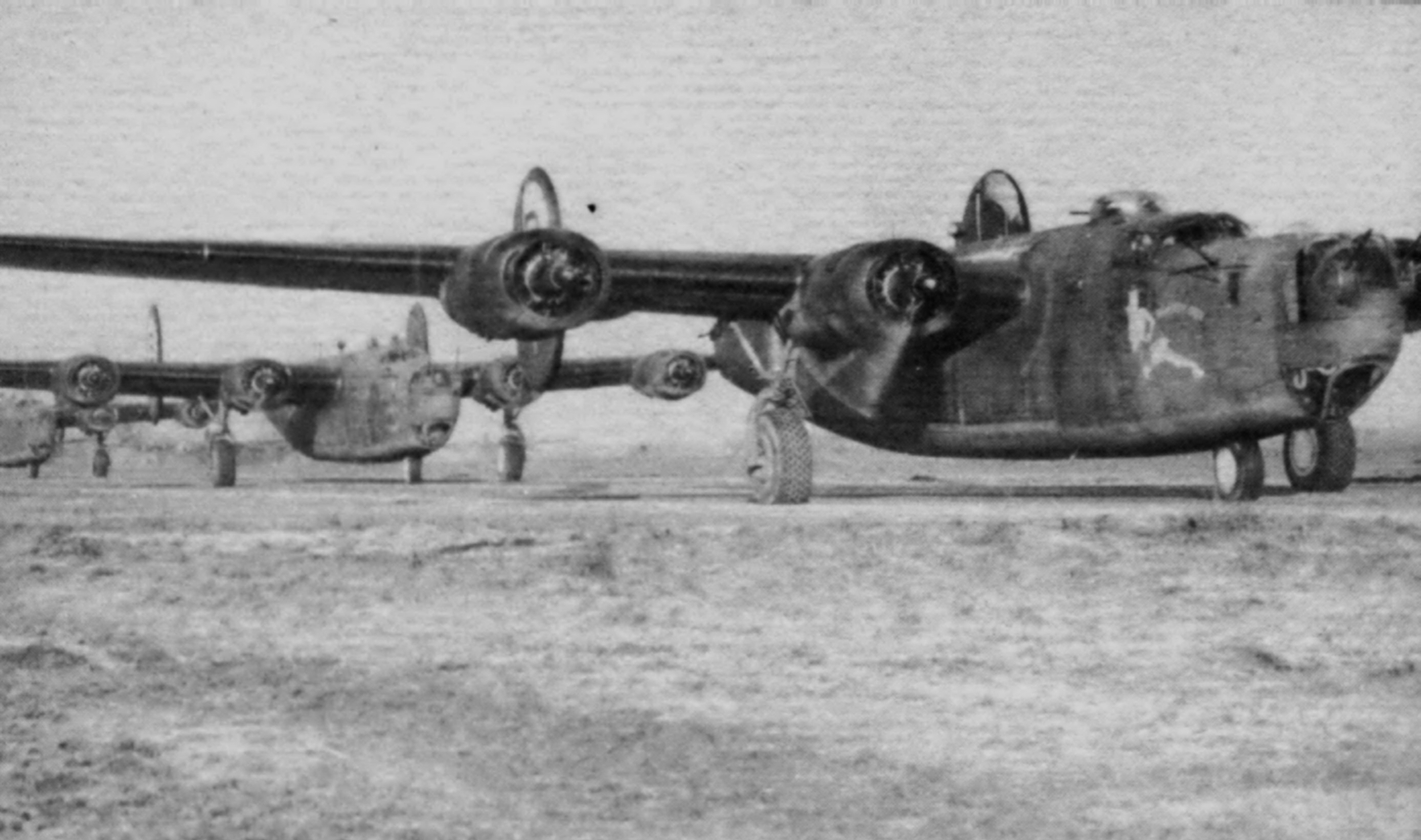

Naughty Nan on the way to Fredrickshaven, the B on the tail is the 93rd Tail code and the GO represents the 328th BS.

The 328th taxiing out at Hardwick, with Naughty Nan in the lead.

at Barksdale Field, near Shreveport, Louisiana under the command of 1st

Lt. Robert M. Tate. Later in the month command of the group was assumed

by Lt. Col. Edward J. Timberlake, a West Point graduate and the son of

a career Army officer whose two brothers

were also officers. Timberlake came to the 93rd from the 98th. By October, 1943 all three would be wearing the

stars of brigadier generals and Edward, who went by Ted, would be the

youngest American general since the Civil War. To staff the group's

four squadrons, the 328th, 329th, 330th and 409th Bombardment

Squadrons, a cadre of personnel was transferred in from other groups

and the 93rd began training with the 44th BG, which had equipped with

B-24s the previous year and which had just transferred to Barksdale

from McDill Field, Florida to serve as an operational training unit for

B-24 crews. Training missions were flown out over the Gulf Mexico where

the crews kept a lookout for German U-boats, which were operating in

American waters at the time. By mid-May the group had become

operational and made the first of many moves as it traveled east to Ft.

Meyer, Florida for antisubmarine duty and remained there through July.

During the group's three-month stay in Florida, 93rd crews were given

credit for sinking three U-boats, one of which was claimed by the crew

commanded by Lt. John L. Jerstad, who had been given the nickname

"Jerk."

at Barksdale Field, near Shreveport, Louisiana under the command of 1st

Lt. Robert M. Tate. Later in the month command of the group was assumed

by Lt. Col. Edward J. Timberlake, a West Point graduate and the son of

a career Army officer whose two brothers

were also officers. Timberlake came to the 93rd from the 98th. By October, 1943 all three would be wearing the

stars of brigadier generals and Edward, who went by Ted, would be the

youngest American general since the Civil War. To staff the group's

four squadrons, the 328th, 329th, 330th and 409th Bombardment

Squadrons, a cadre of personnel was transferred in from other groups

and the 93rd began training with the 44th BG, which had equipped with

B-24s the previous year and which had just transferred to Barksdale

from McDill Field, Florida to serve as an operational training unit for

B-24 crews. Training missions were flown out over the Gulf Mexico where

the crews kept a lookout for German U-boats, which were operating in

American waters at the time. By mid-May the group had become

operational and made the first of many moves as it traveled east to Ft.

Meyer, Florida for antisubmarine duty and remained there through July.

During the group's three-month stay in Florida, 93rd crews were given

credit for sinking three U-boats, one of which was claimed by the crew

commanded by Lt. John L. Jerstad, who had been given the nickname

"Jerk."In May, 1942 the Eighth Air Force transferred from Savannah, Georgia to England to become the headquarters unit for US Army Air Forces units operating in Europe (a small headquarters which became VIII Bomber Command made the move in February.) The 93rd was selected to become the first heavy bomber group equipped with the new B-24 to move to England. The group followed three B-17 groups that moved overseas in July and August. ( It was not the first B-24 group to move to the European Theater. The 98th had moved to Egypt in July where it joined Middle East Air Force and the 1st Provisional Group, a group made up of the B-24s of a special project led by Col. Harry Halverson that had been on the way to China for operations against Japan, and a squadron of B-17s Brereton had brought with him from India.) In preperation for the move, the men of the 93rd moved north from Florida to Grenier Field, New Hampshire where they received a full complement of brand-new B-24Ds, which had been flown there from the factory by ferry pilots. On September 5 the first flight of Liberators departed for England but only got as far as Newfoundland where they were forced to divert due to bad weather. After four days in Newfoundland, 18 Liberators left on a non-stop eight hour flight to Prestwick, Scotland. The flight was the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic by US bombers - the B-17s had to stop off in Iceland due to their much shorter range. One airplane and crew was lost during the crossing, which was made through thunderstorms and icing conditions. For the next month the group was in training at its new base at RAF Alconbury.

On October 8 Col. Timberlake and Major Addison Baker led the group on its first mission, a "milk run" to Lille on the French-Belgian border to attack a steel mill. Although the mission was a "milk run" in comparison to later missions VIII Bomber Command would fly, opposition to and from and over the target was heavy. The group suffered its first combat loss when Captain Alexander Simpson's airplane was shot down. Lt. John Stewart brought his B-24 home with so many holes in it that the crew chief, Master Sgt. Charles Chambers, exploded, "Lieutenant! What the hell have you done to my ship?" Chambers repaired the 200 holes and the crew gave the airplane the name Bomerang because it kept coming back. Part of the crew that was shot down managed to bail out and became prisoners and one, Lt. Arthur Cox, managed to evade and was probably the first Eighth Air Force bomber crewmen to escape to a neutral country, in this case, Spain. Group crews reported from 40-50 German fighter attacks and gunners claimed six shot down, five probables and four damaged. Perhaps surprisingly, the Lille mission was the first Eighth Air Force mission to encounter heavy opposition. All of the previous missions flown by B-17s had truly been "milk runs." John Jerstad cracked everyone up when he commented "that's the worst flak I've ever seen!"

Due to the tremendous losses to U-boats, VIII Bomber Command was directed to mount a series of attacks on submarine pens on the French coast. In November the 93rd flew eight missions, but suffered no losses. That month the 93rd joined by the 44th, which had arrived in England in October and began flying combat in November. In October the 330th BS was detailed to fly antisubmarine missions with RAF Coastal Command. Squadron crews patrolled all the way from Northern Ireland to Algiers on nine-ten hour missions. The B-24s were frequently attacked by Luftwaffe fighters. Maj. Ramsey Pott's crew show down two Junker Ju-88s and claimed another probable over the Bay of Biscay. In one incident Captain Robert "Shine" Shannon, who had flown fighters before he joined the 93rd, took off after a JU-88 he saw in the distance. But although the missions were important in that they caused the German navy headaches, not a single U-boat was ever sighted, much less sunk. On November 13 the group was treated to a visit by His Majesty, King George VI, who was making his first visit to an American installation. He was wearing an RAF marshall's uniform for the occasion. After visiting with the senior group officers in Timberlake's office, the king was taken to the flight line to inspect Teggie Ann, operations officer Maj. Keith Compton's personal airplane, which he had named for his wife, and the group "flagship." Timberlake and Jerstad had flown it on the first mission and it had become the group's lead plane.

Shortly after the group arrived in England Corporal Cal Stewart, who had come over as a radio operator, began publishing a newspaper he named "The Liberator." The former Nebraska newspaperman's talents were quickly realized by Timberlake, who eventually gave him a commission and made him his personal aide. The Liberator was the first military newspaper published in England, and went into print several months before Stars and Stripes and YANK became familiar sights around military posts. Stewart wrote the stories and took the photographs and had the paper printed by a local newspaper after setting the type himself. The paper was not submitted to the censors and the base intelligence officers wouldn't touch it, but they did allow 93rd personnel to send copies back home.

Among

the 93rd personnel was one young airman who stood out. Nebraskan Ben Kuroki

joined the group in April, 1942 while it was still being formed and was

assigned to the 409th as a clerk-typist. He had not experienced

prejudice as he was growing up, but his Japanese ancestry made him a

target after he joined the Army - Ben and his brother had tried to

enlist the day after Pearl Harbor but had to wait for a month until the

Army had decided how to handle Japanese-Americans. A senior 93rd NCO

tried to get rid of him by redlining his name off of the movement order

to Ft. Meyers but he appealed to the squadron adjutant and was

reinstated. He was redlined again on the group overseas order. This

time he appealed to the chaplain. Timberlake himself said that the

young Nisei was going. Ben's clerk duties were in the 409th

orderly room, but he wanted to fly and started spending as much time as

he could out on the flight line, usually hanging out with the armorers.

He was no stranger to firearms; as a boy he had hunted ducks and was a

pretty good shot. The armorers let him work on the guns with them and

he soon was familiar with the Browning .50-calibers. They even let him

test fire the guns. The Air Corps had yet to establish a formal gunnery

training program and pilots picked their gunners from non-flying

enlisted men in the squadron - enlisted crewmembers consisted of the

aerial engineers, who had maintenance training, and radio operator. Ben

finally got his chance to fly when Mississippian Lt. Jake Epting's

tailgunner was medically grounded. Epting picked Ben, and he was placed

on flying status and promoted to sergeant, with an effective date of

December 7, 1942. Ben would go on to complete a 30-mission tour in

B-24s, then went to the Pacific as the only Nisei to fly bombing

missions against Japan in B-29s.

Among

the 93rd personnel was one young airman who stood out. Nebraskan Ben Kuroki

joined the group in April, 1942 while it was still being formed and was

assigned to the 409th as a clerk-typist. He had not experienced

prejudice as he was growing up, but his Japanese ancestry made him a

target after he joined the Army - Ben and his brother had tried to

enlist the day after Pearl Harbor but had to wait for a month until the

Army had decided how to handle Japanese-Americans. A senior 93rd NCO

tried to get rid of him by redlining his name off of the movement order

to Ft. Meyers but he appealed to the squadron adjutant and was

reinstated. He was redlined again on the group overseas order. This

time he appealed to the chaplain. Timberlake himself said that the

young Nisei was going. Ben's clerk duties were in the 409th

orderly room, but he wanted to fly and started spending as much time as

he could out on the flight line, usually hanging out with the armorers.

He was no stranger to firearms; as a boy he had hunted ducks and was a

pretty good shot. The armorers let him work on the guns with them and

he soon was familiar with the Browning .50-calibers. They even let him

test fire the guns. The Air Corps had yet to establish a formal gunnery

training program and pilots picked their gunners from non-flying

enlisted men in the squadron - enlisted crewmembers consisted of the

aerial engineers, who had maintenance training, and radio operator. Ben

finally got his chance to fly when Mississippian Lt. Jake Epting's

tailgunner was medically grounded. Epting picked Ben, and he was placed

on flying status and promoted to sergeant, with an effective date of

December 7, 1942. Ben would go on to complete a 30-mission tour in

B-24s, then went to the Pacific as the only Nisei to fly bombing

missions against Japan in B-29s.In early December Timberlake was ordered to take his group - less the 329th which had been picked for a special mission - south to North Africa. Timberlake was told that the temporary duty (TDY) would be for ten days; the three squadrons were gone for three months. The crews were told to travel light as they wouldn't be gone long. Ground personnel remained behind in England. One crew from the 330th was lost when their airplane hit a mountain while landing at their temporary base at Tafaroui. Personnel at the base had not been alerted that the B-24s were coming in and no plans had been made to light up the runway. Fortunately, the first flight of Liberators landed just before dark and arranged to have gasoline flares lit alongside the runway. As it turned out, winter rain turned Tafaroui - "where the mud is always gooey" into a sea of mud. Timberlake protested in vain to Twelfh Air Force commander Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle, who had won fame as an air racer before the war then had led a raid on Japan, that the field was impossible but Doolittle insisted that a mission be flown on December 12. When the first airplane to take off, Geronimo, mired up in the mud while taxiing to the runway and broke off the nose gear the planned mission was cancelled. The group flew two missions to Bizerte on December 13 and 14, but Eighth Air Force commander Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, decided that the 93rd could be better utilized with Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton's Ninth Air Force, which included two groups equipped with B-24s operating out of Egypt. The 376th BG included one squadron of B-17s to Spaatz worked out a trade; the Ninth B-17s transferred permanently to Doolittle's Twelfth Air Force and the 93rd was attached to IX Bomber Command. Early on the morning of December 15 the 93rd took off for its new temporary home at Gambut Main, a desolate airfield in the Libyan desert. In his diary Brereton described Gambut as to remote that there was literally nothing there except for one metal building. IX Bomber Command, which was commanded by Ted Timberlake's older brother Patrick, was using it as a staging base for missions further west. They would come in, set up a temporary camp, fly the mission then everything would go back to Egypt. After the 93rd joined IX Bomber Command, the group operations officer, Major Keith Compton, was promoted to lieutenant colonel and transferred to the newly established 376th to take over as group commander. The 376th had been formed overseas from the 1st Provisional Bombardment Group, which Brereton had established to control the HALPRO contingent of B-24s that had been on their way to China and the squadron of B-17s he had brought with him from India in June.

While the rest of the group was in Africa, the 329th was training for a new mission called "Moling." The squadron's airplanes were modified by the installation of newly developed electronic navigation equipment that allowed the crews to operate in inclimate weather. The Moling concept was for the modified bombers to penetrate deep into hostile airspace as intruders. Although the missions weren't expected to cause significant damage, they were planned to disrupt the German air defenses and provoke air raid warnings which would cause factory workers to go to shelters. Up to this point no American bombers had yet penetrated German air space. A 329th crew went out on what would have been the first mission to Germany but after flying across France in clouds, they suddenly broke out into the clear as they neared the frontier. Since they had lost their cloak of clouds, the crew had no choice but to abort the mission. Consequently, a few days later a formation of B-17s had the honor being the first to bomb Germany. The 329th worked with British engineers to refine the navigational equipment, which was designated as H2S and Gee, which the RAF had been using on its pathfinder aircraft. The systems were adopted by the USAAF to equip pathfinder B-24s and, later, B-17s.

The 93rd remained in Libya until late February. During their time in North Africa 93rd crews were credited with sinking seven Axis merchant ships and damaging several others. Their bombs destroyed dozens of German and Italian planes on the ground as well as railroad cars and bridges and supply depots. Missions were flown against German supply depots in western Libya and Tunisia and to European targets in Greece, Sicily and Italy, including Naples. During the group's absence the ground echelon and the 329th had relocated to a new base at Hardwick and was where the group returned. While they were gone YANK newspaper had been established and PIO Cal Stewart invited the press out to Hardwick. Censorship prevented the revelation of unit designations to Stewart invented the sobriquet "Ted's Travelling Circus," using the British spelling with two l's. Group personnel weren't allowed to say where they had been or what they had done, but the 93rd suddenly became notorious, much to the chagrin of the 44th Bombardment Group, which had remained in England, and VIII Bomber Command's B-17 groups. Stewart had been told by an Eighth Air Force publicity officer to "work for the entire Eighth Air Force or else" and The Liberator was renamed "Stars and Stripes" and developed into a large scale overeseas military newspaper enterprise - which is still in existence. One crew, Lt Jake Epting's, which included Ben Kuroki, had crashlanded in Spanish Morroco due to bad weather and the crew was interned in Spain until they were finally released and returned to US control. After he returned to England, Kuroki was interviewed by radio personality Ben Lyon.

During the 93rd's absence, the 329th had often operated on conventional bombing missions in company with the 44th BG, which had become operational in November. The 44th had suffered heavy losses, but most were due to accident rather than enemy action. At the time there were no other B-24 groups in Europe and the new groups that were coming in were equipped with B-17s. The B-24 was a new design that had been developed to replace the older B-17, which had not measured up to the requirements under which it had been originally purchased. The British had refused to accept B-17s under Lend-Lease after an initial test squadron failed miserably, but had opted for the new Liberator instead. Consequently, when war broke out only a handful of B-24s had been assigned to US units as most of the production was going to the RAF and the first new groups equipped with B-17s. By the end of 1943 all new groups were equipping with B-24s but in the spring, that was still in the future.

In May Col. Timberlake left the 93rd and moved up to take command of the 201st Provisional Bomb Wing, which had been created as a command unit for the 44th, 93rd and 389th, which was preparing to move to England from the US. Command of the 93rd went to Lt. Col. Addison Baker, who had been commander of the 328th. May also saw a tragedy when Hot Stuff, the first Eighth Air Force bomber to complete a combat tour, crashed in Iceland. The flight is still shrouded in mystery because Lt. Gen. Frank Andrews, the senior US Army officer in the ETO and an airman, was on board along with several other dignitaries. Gen. Andrews and the other dignatries bumped part of Captain Robert "Shine" Shannon's crew off of the flight, including the copilot. (Another 93rd officer was on board who has not been identified except by name - he may have also been a pilot. Andrews himself was an accomplished pilot and skilled in instrument flight. While commander of the GHQ Air Force, Andrews had pushed for instrument training for all combat pilots.) The airplane crashed in bad weather after making several attempted instrument approaches. No official reason has ever been given for Gen. Andrews trip, but it is believed that he had been called back to Washington for a conference. Andrews was a favorite of US Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall and had been Marshall's first choice to head up the Army Air Corps in 1939, but he had been overridden because of Andrews' outspoken advocacy of the four-engine heavy bomber. Marshall later indicated that he wanted Andrews as the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, but his untimely death led to the appointment of Dwight Eisenhower. Shannon's crew was returning to the States as the first Eighth Air Force crew to complete a combat tour, but it had only been recently that such a tour had even been established. Airmen in Europe were under the understanding that they were there for the duration or they were lost, whichever came first. Army Air Forces chief General Henry H. Arnold visited the 93rd at Hardwick in late April. While addressing the crews, Arnold commented that completion of 25 missions constituted a tour of duty and entitled a man to R&R in the US before reassignment. Several men in the room had already flown more than 25 missions by that time. Shannon's crew was one - they had flown their 31st and final mission on March 31st.

Immediately after the 201st PBW activated the 44th and 93rd were taken off of operations for training. The newly arrived 389th also joined in the training, which was conducted in secret and included hours of low-level practice flying. Rumors spread through the B-17 groups that the B-24s were being removed from combat because they were "no good." It was just that, a rumor. In reality, the B-24s were destined to fly what is now the most famous mission of World War II, a daring low-altitude attack on the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. The operation, which was originally code-named SOAPSUDS, was first discussed at the Casablanca Conference in early 1943. Ninth Air Force commander Gen. Brereton was advised of it, and did not think it was a good idea at the time as the Allies were still heavily engaged in combat operations in Tunisia and were planning to invade Sicily as soon as North Africa was secure. Planning for the mission was underway in Washington under the supervision of Col. Jacob Smart, a project officer assigned to Arnold's staff. In June, after the Allied victory in Tunisia, Brereton was informed that the operation was on, and that his IX Bomber Command would carry it out as the B-17s were inadequate for the task. IX BC would be augmented by the three Eighth Air Force B-24 groups. Brereton recorded in his diary that the Ploesti operation was actually planned to be a campaign consisting of a large-scale attack at low altitude followed by up to eight conventional high altitude missions to complete the destruction of the refinery complex. By July the operation had been given a new name, TIDAL WAVE, and Brereton set up a planning staff which included Timberlake, who had moved to Libya by that time. Brereton had the option of flying the mission at low or high altitude, but decided that a low altitude attack would catch the Germans by surprise. Low altitude attacks by B-24s was not without precedent - crews from the 376th had been making low-altitude attacks in Italy for some time. When Brereton met with the five group commanders and informed them of the plan, he advised them that the low-altitude attack decision was solely his and was not open for discussion.

TIDAL WAVE was not the sole purpose of the TDY of the B-24s from England to Libya. The Allies were planning to invade Sicily on July 9 and the three groups would join with IX BC's two groups on attacks in Italy in preparation for the invasion. On July 19 the five B-24 groups attacked railroad yards in Rome in concert with Doolittle's B-17s and Martin B-26s, which were now part of an Allied Northwest Africa Strategic Air Force under Spaatz' Northwest Africa Air Force. After the Rome mission the five B-24 groups were taken off of operations for TIDAL WAVE, which was scheduled for August 1. The mission almost didn't come off. RAF Air Chief Marshall Arthur Tedder wanted to cancel it when Mussoloni was deposed, but Brereton convinced him that to do so would be a mistake for several reasons. The Axis were getting the bulk of their POL supplies from Ploesti which was reason enough, but Brereton also feared that cancelling the mission would cause a severe morale blow for the crews, who had been training for several weeks.

The Ploesti missionis often considered to have been a military disaster, but in truth casualties were no more than those taken by B-17s on high level missions over Germany. The lead group, which was being led by 376th commander Col. K.K. Compton - Compton had stayed in Africa to take command of the newly activated 376th after the 93rd's first African TDY - with IX BC commander Brig. Gen. Uzal Ent on board as an observer, mistook a check point in the summer haze and mistakenly turned about 20 miles too soon and headed toward Bucharest. Lt.

Col.

Baker realized the 376th had turned early and after

following the lead group for several miles, decided to break away and

go after the refineries, which he could see in the distance. He was not

in position to hit his assigned target but went after the nearest

complex as a target of opportunity. Baker's

copilot was Maj. John Jerstad, who had moved up with Timberlake to the

201st and had been the principle planning officer for the mission.

Although the mission had been planned in hope of obtaining complete

surprise, the German air defenses had realized that a large mission was

underway and had deducted that the Ploesti oil fields were the likely

targets. Antiaircraft gunners around the complex were on the alert

while German and Romanian fighter pilots were waiting to be scrambled.

Several batteries of automatic antiaircraft (AAA or Triple A) guns had

been installed in

and around the refineries along with a number of large caliber

antaircraft guns, which could be depressed to fire at low-level

aircraft. Barrage balloons loomed over the target. As the Circus

formation approached their improvised target - they

were not in a position to attack the one they had been assigned - heavy

antiaircraft fire came up to greet them. The B-24 gunners - including

Ben Kuroki who was flying in the top turret on Tupelo Lass,

Col.

Baker realized the 376th had turned early and after

following the lead group for several miles, decided to break away and

go after the refineries, which he could see in the distance. He was not

in position to hit his assigned target but went after the nearest

complex as a target of opportunity. Baker's

copilot was Maj. John Jerstad, who had moved up with Timberlake to the

201st and had been the principle planning officer for the mission.

Although the mission had been planned in hope of obtaining complete

surprise, the German air defenses had realized that a large mission was

underway and had deducted that the Ploesti oil fields were the likely

targets. Antiaircraft gunners around the complex were on the alert

while German and Romanian fighter pilots were waiting to be scrambled.

Several batteries of automatic antiaircraft (AAA or Triple A) guns had

been installed in

and around the refineries along with a number of large caliber

antaircraft guns, which could be depressed to fire at low-level

aircraft. Barrage balloons loomed over the target. As the Circus

formation approached their improvised target - they

were not in a position to attack the one they had been assigned - heavy

antiaircraft fire came up to greet them. The B-24 gunners - including

Ben Kuroki who was flying in the top turret on Tupelo Lass,

Epting's new B-24 - engaged the flak towers to suppress the fire. The

converging tracers hit the gasoline and oil storage tanks on the

outskirts of the refinery and set them afire. While still two miles

from a practical bomb release point, Baker's Hell's Wench

was hit several times and set on fire. It was reported later that Baker

had said the night before that even if his airplane was hit, he'd make

every effort to lead the group over the target - he made good on his

word. The pilots jettisoned the bombs to lighten the load so the

stricken Liberator could keep flying and kept going. After passing over

the refinery Baker and Jerstad pulled their airplane into a steep climb

to gain altitude to give the crew a chance to bail out, then the

airplane fell off on a wing and crashed in a field. Other crews could

see flames in the cockpit of the stricken B-24 when it went down. For

their actions, Baker and Jerstad were both awarded the Medal of Honor,

or the Congressional Medal of Honor as it was commonly known at the

time. All told, 53 Liberators failed to return from the mission,

although that number includes eight that made their way to Turkey where

the airplanes were confiscated and the crews returned. The 93rd lost

eleven. Results of the missions were actually much better than is

commonly reported. Initial estimates were that 60% of the refineries'

capacity was destroyed, although this estimate was downgraded to 40%.

One refinery never returned to operation. (Hundreds of thousands of

words have been devoted to the Ploesti mission, with most authors

trying to come up with an "explanation" for the "wrong turn." They

can't see the forest for the trees. The mission was flown, the target

was hit and severely damaged - which is all that can really be expected

from any military operation.)

Epting's new B-24 - engaged the flak towers to suppress the fire. The

converging tracers hit the gasoline and oil storage tanks on the

outskirts of the refinery and set them afire. While still two miles

from a practical bomb release point, Baker's Hell's Wench

was hit several times and set on fire. It was reported later that Baker

had said the night before that even if his airplane was hit, he'd make

every effort to lead the group over the target - he made good on his

word. The pilots jettisoned the bombs to lighten the load so the

stricken Liberator could keep flying and kept going. After passing over

the refinery Baker and Jerstad pulled their airplane into a steep climb

to gain altitude to give the crew a chance to bail out, then the

airplane fell off on a wing and crashed in a field. Other crews could

see flames in the cockpit of the stricken B-24 when it went down. For

their actions, Baker and Jerstad were both awarded the Medal of Honor,

or the Congressional Medal of Honor as it was commonly known at the

time. All told, 53 Liberators failed to return from the mission,

although that number includes eight that made their way to Turkey where

the airplanes were confiscated and the crews returned. The 93rd lost

eleven. Results of the missions were actually much better than is

commonly reported. Initial estimates were that 60% of the refineries'

capacity was destroyed, although this estimate was downgraded to 40%.

One refinery never returned to operation. (Hundreds of thousands of

words have been devoted to the Ploesti mission, with most authors

trying to come up with an "explanation" for the "wrong turn." They

can't see the forest for the trees. The mission was flown, the target

was hit and severely damaged - which is all that can really be expected

from any military operation.)After the Ploesti mission, the five groups stood down so their airplanes could be repaired. Dozens of new engines were flown in from depots on Air Transport Command C-87 transports - the C-87 was derived from the B-24D. Just because Ploesti had been attacked did not mean that the Eighth AF B-24s were through in the Mediterranean. In fact, the plan had been to mount a campaign against the oil fields but ACM Tedder notified Brereton that the campaign would be delayed and the focus would shift to attacks in Southern Europe. It wasn't until the following April that attacks on Ploesti were resumed by B-17s and B-24s assigned to Fifteenth Air Force, which activated in Italy a few months after the low-level attack. IX BC flew two missions against the aircraft factories at Weiner-Neustad, Austria. Col. Leland Fiegel, who had been with the 93rd in the US, was brought over to take command of the grouip. After an attack on Naples on August 21, the three Eighth Air Force groups were released to return to the UK. Less than a month later Timberlake took his wing back to North Africa, this time to Tunis, for operations against targets in Italy and Austria. The Eighth Air Force B-24s operated out of Tunisia until the end of September then returned to England, this time for good.

For the 93rd, the group was entering what was essentially a brand new war. Nearly all of the group's original combat crews had returned home after completion of their combat tours with only those who had moved to staff positions remaining. The ground crews were not subject to rotation and remained, seeing their airplanes flown by one crew after another as they finished their tour and returned home. A major reorganization took place as the Ninth Air Force moved to England to become a tactical air force to support the upcoming Normandy invasion - Ninth would eventually become the largest US air force in history. It's B-24s transferred initially to Twelfth, then became part of a new Fifteenth Air Force commanded by Jimmy Doolittle. More and more B-24 groups were arriving in England and Second Air Division was established to control them. The 93rd became part of the 20th Combat Bombardment Wing, one of three wings equipped with B-24s. In early 1944 Eighth Air Force headquarters was elevated to become United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, a new organization that would control all strategic air operations in the European Theater. VIII Bomber Command was elevated to air force level and redesignated as a new Eighth Air Force. Both units activated in February, 1944. In the reorganization Eighth Air Force commander Ira Eaker was promoted to lieutenant general and sent to the Mediterranean to replace Tedder, who had been appointed deputy commander under Eisenhower of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Forces in Europe. Jimmy Doolittle was brought to England to take his place. By June 6, 1944 Eighth Air Force B-24 strength had built up to nineteen groups, only four less than the twenty-three groups of B-17s. Army Air Forces intentions were to replace all B-17s with B-24s but for some reason Doolittle opposed the move and wanted to convert Eighth Air Force entirely to B-17s. More replacement B-17s were arriving in England than needed so he took them and began converting the B-24 groups in the 3rd Air Division. His plan to convert all groups was thwarted by a cessation of B-17 production and the impending end of the war, with the corresponding decline in importance of strategic bombardment.

The war effort in Europe in late 1943 was now focusing on making preparations for the upcoming Normandy Invasion. In his New Years message to Eighth Air Force, Arnold had stated that the mission was to "destroy the German air force in the air, on the ground and in the factories." Throughout 1943 bomber missions into Germany had been flown without escort, and mounting casualties led to a suspension of deep penetration missions until escort fighters became available that could make their way all the way to the targets. Such aircraft were under development as external fuel tanks were developed for the Republic P-47s that were serving as the primary escorts. Long-range Lockheed P-38s, all of which had been diverted to Africa, became available for escort duty from England. R&D expert Brig. Gen. Ben Kelsey had spearheaded the development of a new version of the North American P-51 Mustang that also had the range to go all the way to Berlin and other targets deep in Germany. However, it is a myth that bomber losses began declining with the advent of the escort fighter, particularly the P-51. In fact, losses began increasing. By April 1944, losses exceeded 400 airplanes. The B-24 had also undergone development. In an effort to ward off the head-on attacks favored by German, Italian and Japanese fighters, a new nose turret installation had been developed to replace the glass nose on the D-models. The new turrets produced additional drag and reduced the B-24s airspeed by about 20 MPH, but the Liberators were still a good 20 MPH faster than the B-17G, and could carry a much larger payload over greater distances.

In preparation for the invasion, Spaatz' USSTAF planned a massive campaign of attacks on the German aircraft industsry by Eighth and Fifteenth Air Force B-17s and B-24s, a campaign that came to be known as "Big Week." New bomber tactics involved the use of pathfinder B-24s as lead airplanes in bomber formations. The pathfinder airplanes, which in the 93rd were assigned to the 329th, were equipped with radio navigational equipment and radar and radar operators and radar bombardiers were included in their crews. Although Eighth Air Force senior officers still talked about "precision" bombing, it had actually adopted the British model of using pathfinders to find the target. The difference was that daylight missions depended on lead crews who would determine the release point, with the rest of the bombers in the formation dropping when they did. British missions were flown exclusively at night and the pathfinder crews lit up the target with incindaries and flares. Incindiary bombs were also included in B-17 and B-24 bomb loads.

Prior

to Big Week the 93rd flew several missions aimed at the German rocket

launching sites in France, but the new  emphasis was on the aircraft

industry. In early March the egocentric Doolittle mounted a series of

attacks on the German capital city of Berlin, which had yet to see

American bombers overhead. Doolittle wanted to lead the raid so

headlines would read that he had bombed all three Axis capitals - he

led the raid on Tokyo then participated in the first raid on Rome - but

Spaatz put his foot down and grounded the ambitious general. As it

turned out, the March 6 mission to Berlin was the costliest mission of

the war for Eighth Air Force. Sixty-nine bombers, mostly B-17s, were

shot down by fighters. A second mission two days later cost 37. Two

missions cost Eighth Air Force over 100 B-17s and B-24s and their

crews. Eleven fighters were lost on the first mission and seventeen on

the second, bringing total personnel loses to nearly 1,100 men. That

figure does not include the men who were KIA on airplanes that returned

from the mission. The airplane losses were also considerably heavier as

large numbers returned to their bases too shot up to ever fly again. On

April 1, 1944 the USSTAF came under the direct command of SHEAF when the Combined Bomber Offensive reached it's planned end and

from that time on, all heavy bomber operations were under Eisenhowers

direct command although the line of command was through Spaatz.

Transportation targets - railroads, marshalling yards, etc. became

primary targets along with airfields and other installations in France.

Raids on aircraft factories continued. Buzz bomb and rocket launching

sites were also attacked with considerable frequency. On April 4 Bomerang departed for the United States where it would go on a warbond tour. The 93rd's squadrons now operated B-24Hs and Js.

emphasis was on the aircraft

industry. In early March the egocentric Doolittle mounted a series of

attacks on the German capital city of Berlin, which had yet to see

American bombers overhead. Doolittle wanted to lead the raid so

headlines would read that he had bombed all three Axis capitals - he

led the raid on Tokyo then participated in the first raid on Rome - but

Spaatz put his foot down and grounded the ambitious general. As it

turned out, the March 6 mission to Berlin was the costliest mission of

the war for Eighth Air Force. Sixty-nine bombers, mostly B-17s, were

shot down by fighters. A second mission two days later cost 37. Two

missions cost Eighth Air Force over 100 B-17s and B-24s and their

crews. Eleven fighters were lost on the first mission and seventeen on